Science After Bacon

Note: A more concise (but perhaps less exciting) version of this essay can be found here.

Peter Thiel frequently makes the following claim: Since the 1970s, technological progress has been limited to computer science (The World of Bits) and has stagnated elsewhere (The World of Atoms). Thiel’s friend Eric Weinstein has said, “Go into any room today and remove all the screens. How do you know you’re not in 1976, but for issues of design?” There is a lot of truth in this claim and it leaves us with the why question.

In a recent discussion with Jordan Peterson, Thiel begins with a caveat – outcomes like technological stagnation always have multiple causes (that is, why questions are overdetermined). Still, he continues, “It could be that our society became too risk averse, or too feminized, or you could say that there was too much regulation… But I’ve come to think one of the bigger factors was the sense that a lot of the science and technology was quite dangerous. It had a dual use (military and civilian) character… World War One was sort of a breaking point where the naive progressive narrative really got undercut and and then somehow, you can say that the Baconian science project, in some sense, ended – that is, ended in the Hegelian sense, meaning both culminated and terminated – at Los Alamos with the building of nuclear weapons. And then again, it doesn't work perfectly, but my telling would be that it took maybe a quarter century for nuclear weapons to really get internalized by society. And then, by the 1970s, the energy (Zeitgiest) was that we don't want to be doing this – we're not going to build more thermonuclear bombs. (Instead), we’re going to peace out at Burning Man with psychedelic drugs. (Or), we want to escape back to nature through environmentalism. We want to be in a world, not of change, but of stasis, because the world of change has this apocalyptic dimension. Change is change for the worse.”

The claim that the Baconian science project ended (both culminated and terminated) at Los Alamos with the building of nuclear weapons is so significant and so striking that one should take a moment to let it sink in. It is, in a way, a mirror image of Nietzche’s “God is Dead” claim. It is an acknowledgement that the modern priests – that is, the scientists – have lost their claim to authority. Humanity now knows, albeit in a way that is mostly unconscious and rarely said aloud, that the end of the scientific and technological worldview is the atom bomb. And it has opted out, implicitly if not explicitly. One might say that the hostility toward Anthony Fauci and subsequent rise of anti-vaccine skepticism are only later, more extreme manifestations of this underlying distrust toward scientific expertise.

But there is another part of the story. Thiel notes that we may consider “the Apollo space program as the last great technological scientific project. (In) July of 1969, we land on the moon and Woodstock started three weeks later. With the benefit of hindsight, in some sense, that's when progress stopped. Scientific and technological progress stopped, and the hippies took over the country.” So, we may consider the end (i.e., culmination and termination) of the Baconian scientific project to be twofold: nuclear weapons and a man on the moon. The latter is a great triumph for humanity; the former its shadow. Thiel, of course, wanted a spacefaring civilization that does not extinguish itself with nuclear weapons. That is not what we got.

As I said earlier, I mostly accept Thiel’s story of stagnation. I first encountered it while working on the 2020 Biden Presidential campaign. Soon afterwards, I dropped my naively held notions of returning to the saner times of the Obama years. I left the campaign a month or so later.

But, unless Thiel has recently changed his tune, this is where I have differed: Is the correct conclusion, then, that we should restart scientific progress as if these dual-use catastrophes had not happened? Of course not. How could we do so? And Thiel, for the first time publicly in this interview with Jordan Peterson, seems to be sympathetic to that objection.

Thiel continues, “That's the sense I get in the 1970s. The progressive version of science, we tried to push the pause button on it. The places where it's still allowed, you can see, are the most inert. So, in a way, the world of bits was seen as incredibly inert, because you're not building bombs, you're not building weapons with it. And then, of course, there is even some sort of way in which the ideas on the internet translate into reality. Every now and then, what happens on Twitter doesn't always stay there. Most of the time it stays there. So it feels like it's this extremely angry, intense conversation, but every now and then, it still translates to the real world. So, the internet, you could say, was allowed because it was a sort of safe space. It was a place where the violence could be contained – and even there not totally. Even there, people felt it was maybe too much… I don't like the stagnation and the risk aversion and all these responses. But a part of it, I think, is understandable.”

And further, “There is a part of science and technology that has a dark dimension – that it's a trap that humanity may be setting for itself. And, you know, I don't like Greta and I don't like the full precautionary principle, but her argument that we have just one planet isn't entirely wrong.”

And finally, “We got thermonuclear weapons. We really are powerful enough to affect the environment. I'm not sure whether carbon dioxide is the most important dimension, but you know, and they're probably a lot of dimensions where the environment can be impacted in very, very radical ways. We can probably build very dangerous bioweapons – maybe that's even what's going on in the Wuhan lab. There are dimensions of AI that are potentially violent and very dangerous. And you don't have to necessarily believe all these sort of weird pictures where it's this super intelligence that's somehow completely disembodied and is going to kill every last human being on the planet. But there are natural ways to combine it with weapons technology that feel unsettling. A simple example is that we have this drone technology in the forefront in the conflict between Russia and the Ukraine. You have a human in the loop, and the human can get jammed. So, the natural fix is to put AI on the drones and turn these into more autonomous weapon systems. That seems inevitable. That seems like the natural, logical thing to do. And then even I – as a pro tech person – have to say, I find that somewhat unsettling.”

It is both beautiful and remarkable to see Thiel, the face of the tech accelerationist movement, acknowledge these concerns head on. The question remains: If we are not going to pick up scientific progress where we left off, then what do we do instead? I’m going to present two possibilities: (1) The problem is that we (humanity) are not wise enough to properly use what we learned via the scientific method. After all, nuclear energy need not power weapons. It could just as easily be used to power communities. It is possible that a wiser humanity could explore the stars without self-destruction. The answer, then, comes not from blindly reaccelerating technology but from helping humanity become wise enough to use it. Or: (2) There is a problem with the scientific project itself. That is, there is something in Bacon's underlying pursuit that leads naturally to its dual end on the moon and at Los Alamos. This is a very bold claim, and I acknowledge that. But I am quite certain there is something to it, and I will provide some reasoning in the following section. If this is true, we will then need a new epistemology — that is, a new theory of knowledge to replace the scientific method. I do not claim to provide such a method, only to point to its necessity.

The Scientific Project

I will begin the second part of this essay with an excerpt from Valentin Tomberg’s meditation titled “The Empress.” He is far from the only thinker to recognize the roots of the scientific (see CS Lewis, amongst others), but I turn to Tomberg because of the precision and immediacy of his diagnosis.

He wrote, “The practical aspect of the scientific ideal is revealed in the progress of modern science from the eighteenth century to the present day. Its essential stages are the discoveries and putting into man’s service, successively, of steam, electricity and atomic energy. But as different as these appear to be, these discoveries are based only on a single principle, namely the principle of the destruction of matter, by which energy is freed in order to be captured anew by man so as to be put at his service. It is so with the little regular explosions of petrol which produce the energy to drive a car. And it is so with the destruction of atoms, by means of the technique of neutron bombardment, which produces atomic energy. That it is a matter of coal, petrol, or hydrogen atoms, is not important; it is always a case of the production of energy as a consequence of the destruction of matter. For the practical aspect of the scientific ideal is the domination of Nature by means of putting into play the principle of destruction or death.”

Woah! That is quite an assertion. Is it true?

To recognize the scientific ideal one must differentiate the scientific method from the scientific project. The scientist confirms truth with his senses (i.e., empirically) and does not accept inferred truths (i.e., reason) without confirmation from his senses. The truth gathering process is then formalized in the scientific method, which is the repeatable process of positing a hypothesis, performing an experiment to confirm or deny this hypothesis, and recording the results so that others may repeat the process to further confirm or deny. A hypothesis is more likely to be true if both you and I perform the same test and observe the same outcome, and even more so if several others follow suit.

It is a method of gathering information about the world. So, what is the scientific project? And how did Tomberg come to his conclusion about dominating nature?

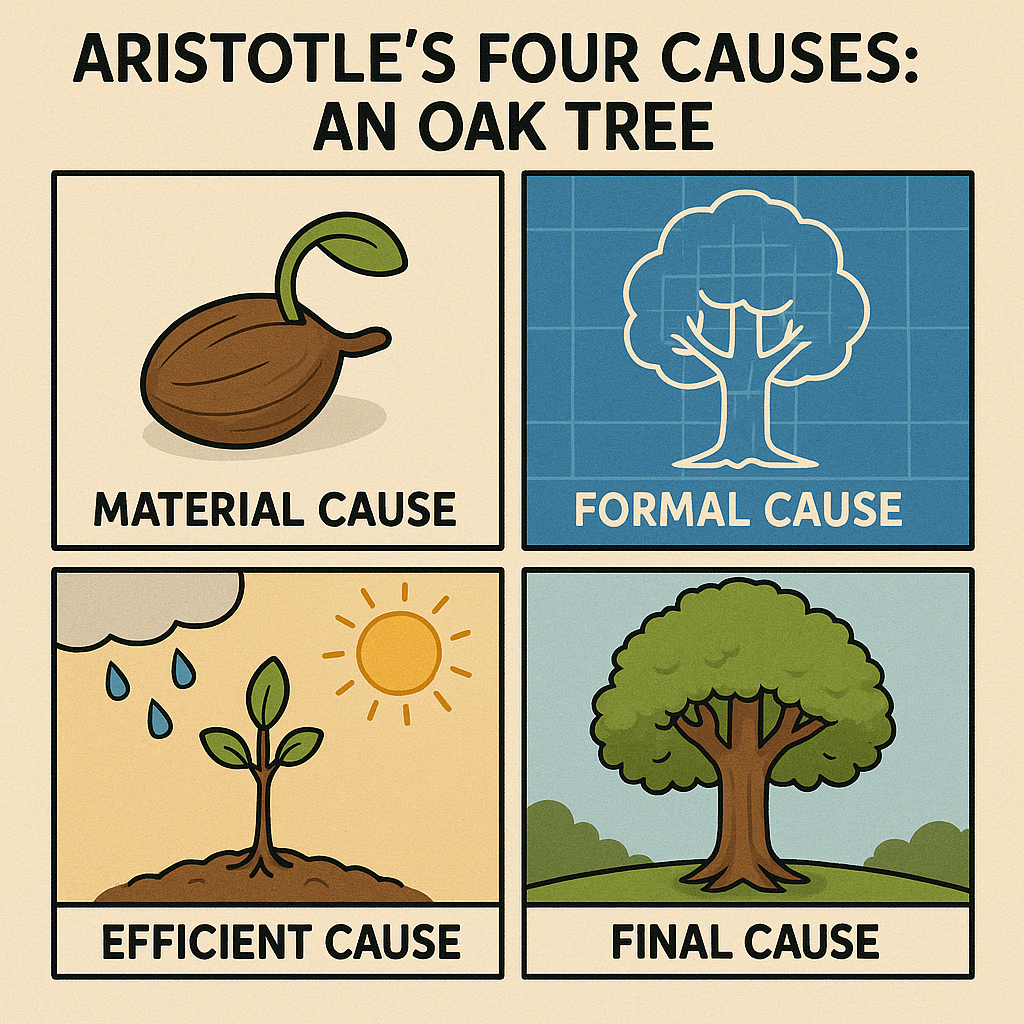

The key to recognizing the scientific project lies in the distinctions between the four Aristotelian causes. Consider the example of a marble statue.

Material Cause: What something is made of (e.g., marble).

Formal Cause: The shape, pattern, or essence that makes a thing what it is (e.g., the statue’s design or image).

Efficient Cause: The agent or force that brings something into being (e.g., the sculptor).

Final Cause: The purpose or goal for which a thing exists (e.g., to honor a god or beautify a temple).

One may quickly note that the scientific method prioritizes material and efficient causes and excludes formal and final causes. That is a consequence of empiricism, which requires confirmation via the senses. Final causes and formal causes are not discernible via the traditional five senses (namely sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing). Distinguishing between these four causes not only allows us to recognize Bacon’s intent, but also to consider alternative methods of knowledge. Why? Because if the scientific method is an examination of material and efficient causes and an exclusion of final and formal causes, the alternatives may be found by focusing on or at least incorporating the latter two.

Let’s turn to Peter Kreeft, philosophy professor at Boston College, in his lecture titled Plato vs. Machiavelli on Political Philosophy, Kreeft says, “final causes are goods, formal causes are essences. These are what Plato sought in each of his dialogs, which ask the question, what is it? What is its essence? And what above all is the good, the end, the value? Both formal causes and final causes have been dropped from most modern philosophy and increasingly from modern consciousness. And the reason is that they have proved distracting in modern science, which deals only with material causes and efficient causes, or forces pushing from below and behind, rather than final causes, which are ideals attracting us with their beauty and goodness and truth from above and ahead.”

Recall Tomberg’s description of the scientific (and technological) ideal: the principle of the destruction of matter, by which energy is freed in order to be captured anew by man so as to be put at his service. In order to achieve this ideal, one must first understand matter (or understand material causes) well enough to systematically destroy it and produce energy (via efficient causes). Then, one must put matter at our service (that is, provide it with a new final cause).

A final cause can either exist naturally or be determined by man. Let us consider the differences in formal and final causes from something that occurs naturally (e.g., humanity or an oak tree) vs. something that is made of free will (e.g., a chair or a ring). This essay was primarily inspired by Peter Thiel and, as we will see later, Mr. Thiel is very much inspired by the Lord of the Rings. So, we will first consider the causes of an oak tree (or one it can imagine to be one of the trees of Lothlórien), then we will consider the causes of The One Ring.

For the oak tree, the material cause is the acorn (from the earth; from below). The formal cause is the oak’s genetic blueprint or DNA — its “oakness” (from the Logos, from above). The efficient cause(s) are rain and sunlight, among other things (from behind), and the final cause is to grow, bear acorns, participate in the forest ecosystem, and fulfill its role in the larger order of life — to embody "oakness" in its highest form (from God’s will, from ahead).

Now let us consider the case of The One Ring. The material cause is the substance — the Mithril (from [middle]earth; from below), mined by the Dwarves in Khazad-dûm, where they delved too greedily and too deep. The formal cause is the form or blueprint of the One Ring (from the mind of Sauron). The efficient cause is the will and craftsmanship of Sauron (from behind), and the final cause is world domination (from the will of Sauron).

Both the oak and the ring consist of materials from the [middle]earth (material causes): an acorn and the mithril. And both were shaped by forces of [middle]earth (efficient causes): Rain/Sunlight and Sauron. Both the oak and ring have forms (formal causes) and purposes for existing (final causes). The difference is that the form and purpose for the acorn were determined by God or nature and the form and purpose of the One Ring was determined by Sauron via his free will.

Again, we return to Keeft, who likens Baconian Science to Machiavelli’s political philosophy. What do they share, according to Kreeft? The underlying Will-to-Power – that is, the underlying intention to dominate or bend to one’s will. “Machiavelli's concluding image of success in The Prince is shocking. He writes, ‘fortune is a woman, and to master her, it is necessary to beat her and strike her.’ The image is strikingly similar to that of Francis Bacon. When he announces the new post religious summum bonum, or greatest good for Western civilization, he says that the highest purpose of man on earth is not – as the naive and inefficient medievals thought – to conform the mind to truth by contemplation and to conform the will to virtue by holiness, not to conform the human soul to the objective reality that is platonic and eternal, but rather to force nature to conform to the will of man by applied science – that is, technology. He called it man's conquest of nature. And Bacon used an image for that success which is strikingly similar to the one Machiavelli uses. It is literally striking. That is hitting, beating. He says that science must learn to put nature to the torture rack and compel her to come out with her secrets… In both cases, power replaces virtue, push replaces pull, force replaces moral appeal, efficient and material causes replace final and formal causes.” In this transformation, the summum bonum becomes not the good life as defined by reason or divine law, but "the relief of man’s estate", as Bacon himself puts it in The Advancement of Learning. It is also worth noting, however briefly, that the reversal of this modern project also underlies the 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous (see step three).

So, the scientific method is a tool for gathering knowledge of material and efficient causes. The information is used for the scientific project, which seeks to use the knowledge gained from the method to, as Strauss wrote, “make nature conform to (man’s) soul—his needs, his desires.”

Strauss’s description implies the intention beneath modern science is the Will-to-Power – in this case, the will to dominate nature. The Will-to-Power is an explicit denial of any final cause endued to nature in favor of a final cause for nature endued by oneself. That – there! – is the distinction between the technological and the Christian projects. The Will-to-Power is most commonly associated with Nietzche, who also coined the phrase “God is Dead.” Insofar as God is Christ, Christ is the Word, and the Word is the Logos or divine ordering principle: The phrase “God is Dead” denies nature’s formal causes (because formal causes are expressions of the Logos or Christ). If “God is dead,” as Nietzsche claimed, then humanity is free to redesign nature (to disregard formal causes), and to do so in alignment with one’s own will (or one’s own final causes).

The Scientific Method

The primary issue is not the examination of material and efficient causes but rather the use of this knowledge to bend nature to our will, which is personal and not in accordance with the whole. There is not anything inherently wrong with examining material and efficient causes. So, we might imagine the scientific project as a two step process: (1) acquire knowledge of nature, (2) apply this knowledge of nature to serve humanity. One is science; two is technology. The error of science is that it only acquires knowledge of material and efficient causes; the error of technology is that it uses the energy for man’s ends rather than the ends of the whole. But one could easily imagine a theory and application of knowledge without these pitfalls. The theory of knowledge could begin by combining Platonic (or Aristotelian) philosophy with our modern scientific corpus and technology could be reoriented towards Plato’s (or Aristotle’s) proper ends.

Still, there is a more subtle concern about the forced revelation of nature through scientific experimentation. This concern is very difficult for modern people to understand, and may need to be put aside at first in favor of the concerns raised earlier (namely, the reincorporation of formal and final causes). Abstractly, most modern people do not consider “nature” to be an entity who might have “terms” of her own. However, in practice, the moderner does recognize cruelty in certain experiments when he sees it, especially when they involve the suffering of animals. Still, I am not dead set against formal experimentation, especially when no obvious harm is done. This is an area where I remain undecided, and have more to learn.

As an example of a “consensual” revelation (for lack of a better term), Leonardo Da Vinci examined nature in a manner that would not fit the analogy of “putting nature to the torture rack.” He discerned the laws of nature strictly through observation rather than formal experimentation. A friend of mine noted that Da Vinci’s method seemed too passive and Bacon’s too aggressive; maybe Da Vinci’s method is too yin and Bacon’s too yang. It is Tomberg who points toward balance between the two. What might that look like? Again, recall Tomberg’s description of the scientific project: “The principle of the destruction of matter, by which energy is freed in order to be captured anew by man so as to be put at his service.” The question then becomes, what if we do not destroy and recreate according to our own wishes? What if instead, we helped things to live? What if we served them, and allowed them to serve us? They would, of course, then reach their natural end, and so might we.

Tomberg lays out this philosophy in the same essay. He calls it Hermeticism. He wrote, “Imagine, dear Unknown Friend, efforts and discoveries in the opposite direction, in the direction of construction or life. Imagine, not an explosion, but rather the blossoming out of a constructive “atomic bomb”. It is not too difficult to imagine, because each little acorn is such a “constructive bomb” and the oak is only the visible result of the slow “explosion”—or blossoming out—of this “bomb”... Now, the ideal of Hermeticism is contrary to that of science. Instead of aspiring to power over the forces of Nature by means of the destruction of matter, Hermeticism aspires to conscious participation with the constructive forces of the world on the basis of an alliance and a cordial communion with them. Science wants to compel Nature to obedience to the will of man such as it is; Hermeticism on the contrary wants to purify, illumine and change the will and nature of man in order to bring them into harmony with the creative principle of Nature (natura naturans) and to render them capable of receiving its willingly bestowed revelation.”

Why can’t we be like the elves?

Finally, let us return again to Mr. Thiel. On the other end of this stagnation, his aspirations do not stop with humanity amongst the stars. The following is an excerpt from Peter’s recent interview with Barton Gellman of The Atlantic, titled, “Peter Thiel is Taking a Break from Democracy,” where he discusses his desire to live forever, and does so in association with his love of The Lord of the Rings. Gellman writes, “More than anything, he (Thiel) longs to live forever…. Did his dream of eternal life trace to The Lord of the Rings? I wondered. Yes, Thiel said, perking up. “There are all these ways where trying to live unnaturally long goes haywire” in Tolkien’s works. But you also have the elves. “And then there are sort of all these questions, you know: How are the elves different from the humans in Tolkien? And they’re basically—I think the main difference is just, they’re humans that don’t die.” “So why can’t we be elves?” I asked. Thiel nodded reverently, his expression a blend of hope and chagrin. “Why can’t we be elves?” he said.”

This is a beautiful exchange – one that struck me to my core. I share Peter’s aspirations. I, too, want to be like the elves. But, upon reading, and re-reading, I came to the conclusion that the main difference is not that they are humans who don’t die. Death, in this instance, is not the cause but the effect. Death is the consequence of sin. What is sin? The term is derived from the Greek word hamartia, which (as JBP never tires of saying) means “to miss the mark.” What is the mark? The final cause, of course! In this manner, the practitioners of the scientific project consciously and intentionally deny the final causes of nature and replace these ends with their own wishes. That is, they consciously and intentionally sin, and thereby cause – nay, guarantee – death. To sin one’s way out of death is a contradiction in terms.

The elves are not putting nature to the torture rack. They are not bending nature to their will. The elves (like Tomberg’s Hermeticists) live in harmony with nature’s creative forces. They do not overcome death through technological mastery. Instead, they do not perform the acts to which death is an inevitable consequence.

This Will-to-Power is exactly what the best of the elves, the Lady Galadriel, denies when the One Ring is offered to her. What does she say? “I pass the test. I will diminish, and go into the West, and remain Galadriel." What does it mean to “remain Galadriel”? To remain true to her essence (her formal cause), and thereby “go into the West” to meet her natural end (her final cause). This statement signifies Galadriel's conscious choice to reject the immense power of the One Ring, opting instead to align with the natural course of the world and accept her place within it. It is this manner of being which allows Galadriel and elves of Lothlorien to live as they live – amongst the trees, and in harmony with them. I hold out hope that newfound wisdom, and its accompanying theory of knowledge, will allow for humanity to do the same.

Returning seven months later, in January of 2026, I now understand this essay to be a call for Goethean science. This became clear to me after I attended a lecture by Jon McAlice of The Nature Institute in November. The Nature Institute is the final remaining foundation for Goethean science. If this essay interests you, please consider supporting their mission.

Godspeed.